Early 16th century Iranian earthenware decorated with pomegranates - in the Louvre. Picture from Wikimedia Commons.

A few posts back I wondered how well you know your brother and posited that, generally speaking, we really do not know those whom we think we know very well indeed.

But here’s another question. If you did not know you were a father (an ignorance no mother can match), and were later to meet your son in circumstances that completely hid his provenance, would you know?

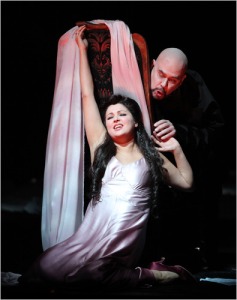

Hasan feels a mysterious attraction to the young lad who comes unannounced into his cookshop in Damascus one day eleven years on from his ‘ifrit-mischief wedding night, and ‘Ajib too feels inexplicably drawn to the bearded stranger offering him food. But once again the audience is left on tenterhooks by the gap between their inside information and the cloud of unknowing enveloping the hapless protagonists.

So near, and yet so far. Is Allah at play? Or is the audience – not, you understand, Ja‘far’s rapt audience of three dervishes, a caliph and a bevy of beauties, nor yet Shahrazad’s bedroom audience of misogynist husband and faithful little sister, but the eager crowd in the dusty market place, pressing in closer the better to hear such marvels – is the audience demanding more, not wanting it to end, not yet, the night is young, so that the storyteller is obliged to add yet another level of delay and convolution to hold off the denouement?

And to do it twice!

It’s not as if we have not already tensed in anticipation as Shams al-Din (a clever man) deduces from the few clothes and possessions strewn around the bridal chamber that the changeling bridegroom is none other than his nephew, and so the rightful destined husband of his daughter after all, and we have shared in his conviction that Hasan must surely return to claim his bride, and in their joint anguish as time passes, and passes, and a son is born the handsome image of his father, and the years go by – and there’s no sign.

Why doesn’t Hasan come back to Cairo? It’s not as if he’s a prisoner over there in Damascus where the jinni dropped him, and we know that his own father got from Cairo to Basra without benefit of jinni, so it can be done. I have forsworn leaping ahead in this blog, but not leaping back, so I carefully reread the account of the wedding night to look for clues. And it appears that not only did Hasan not have the faintest idea of the identity of his bride, he had not the faintest idea where in the world the ‘ifrit and the jinna had brought him. So there was no way back for him.

The storyteller succumbs to the audience’s demands, the encounter between Hasan and ‘Ajib ends in a brawl of misunderstanding and paranoia, the Egyptian party leave for Basra on their quest for the missing husband, oblivious that one of them has already seen the holy grail… oh sorry, different story!

But now they get a second chance. Will they realise this time that what is pulling them together is the call of blood to blood?

No. It’s all going to come down to a cook off.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating, and ‘Ajib is in no doubt that his newly found grandmother’s pomegranate dessert – all her own recipe, you must understand, known only to her long lost son – is far inferior to that of the lowly Damascus cookshop owner who has just stuffed him so full he cannot take another mouthful.

She is not amused.

Are we there yet?